Take a photo of a barcode or cover

120 reviews for:

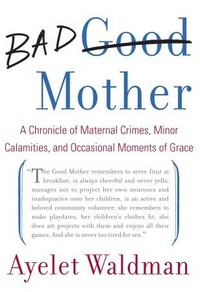

Bad Mother: A Chronicle of Maternal Crimes, Minor Calamities, and Occasional Moments of Grace

Ayelet Waldman

120 reviews for:

Bad Mother: A Chronicle of Maternal Crimes, Minor Calamities, and Occasional Moments of Grace

Ayelet Waldman

There was lots in here that I could relate to and some that I couldn't. Waldman was brave to write what she wrote - a lot of people are going to have a lot of opinions about what she says!

I listened to this on audiobook, and was very engaged. Mothers (and mothers-to-be) suffer a great deal of disapproval -- and even outright attacks -- from others, especially other women (with or without children). Waldman very honestly discusses the expectations mothers have and how these expectations are impossible to fulfill (versus those of being a "good father": be reasonably present and supportive of mom and children). She delves into very personal material, such as the devastating choice to terminate a pregnancy of a child with a rare trisomy. She has taken a lot of flack for an essay about sex after children because she stated that she loved her husband more than her children. All very interesting. I think it's important to realize the ridiculous pressure on women who have children and make an effort to reduce it -- or at least MYOB.

i feel so tricked, i thought this was going to be out mothering/parenting but instead it's all about the author and every aspect of her life is.

Really more a collection of essays than a single narrative, but most of them are really good. I don't agree with everything Waldman has to say, but that plays into her main theme - that we need to stop judging other parents who do things differently than we do.

The parenting shelf at the book store is full of guides on how to be the perfect parent, and this provides some entertaining counter-programming.

The parenting shelf at the book store is full of guides on how to be the perfect parent, and this provides some entertaining counter-programming.

Great memoir, 3 1/2 stars. Waldman is very honest about motherhood and her experiences. She just puts it all out there, which can be much appreciated. I applaud her for being so open about some of the touchier subject issues that have happened to her and her family.

After reading Michael Chabon’s Manhood for Amateurs I discovered that his wife had written what is essentially the same book but from a female perspective, a kind of Motherhood for Amateurs. While I was waiting for it to arrive for pick-up at my library branch I Googled her and realized that this was the woman who went on Oprah and told mothers everywhere that they should put their husbands ahead of their children. That is, it turns out not what she said, but not having seen the show this was the impression I had arrived at after listening to the Internet equivalent of water cooler scuttlebutt. It turns out she has served as whipping girl on various other motherhood issues as well. I suspect that most women would hide away from the vitriol, not Ayelet Waldman.

Like Manhood for Amateurs, Bad Mother is a collection of essays. Through them Waldman covers just about all the motherhood hot buttons, from abortion and breast feeding to the stay at home vs. the working mom debate. This is not an academic overview but a brutally honest and intensely personal accounting of her own, as she puts it, “maternal crimes, minor calamities, and occasional moments of grace”. Would I, personally have made all the same choices she has? No. Was my experience of motherhood exactly the same? No. But, to fixate on the differences or even the similarities (of which, I confess there are many) is largely to miss the point. In fact, she herself makes different choices with different kids at different times and for different reasons.

She is, ultimately, like the rest of us, a woman who loves her kids and does her best. Unlike most of the rest of us she is brave enough to publicly confess some of the things that we might only whisper to our best friends. Horrific things, like being bored numb by Raffi. Yes, she’s been pilloried for that admission. Of all the accusations hurled at her, the one that seems to reoccur with the greatest frequency is that she “overshares”. I see it another way, I think we mothers in general are guilty of “undersharing” and that until more of us are willing to present the unpolished, not always pretty truth of our own experiences with motherhood judgment will continue to trump support and we will all be diminished by it.

Like Manhood for Amateurs, Bad Mother is a collection of essays. Through them Waldman covers just about all the motherhood hot buttons, from abortion and breast feeding to the stay at home vs. the working mom debate. This is not an academic overview but a brutally honest and intensely personal accounting of her own, as she puts it, “maternal crimes, minor calamities, and occasional moments of grace”. Would I, personally have made all the same choices she has? No. Was my experience of motherhood exactly the same? No. But, to fixate on the differences or even the similarities (of which, I confess there are many) is largely to miss the point. In fact, she herself makes different choices with different kids at different times and for different reasons.

She is, ultimately, like the rest of us, a woman who loves her kids and does her best. Unlike most of the rest of us she is brave enough to publicly confess some of the things that we might only whisper to our best friends. Horrific things, like being bored numb by Raffi. Yes, she’s been pilloried for that admission. Of all the accusations hurled at her, the one that seems to reoccur with the greatest frequency is that she “overshares”. I see it another way, I think we mothers in general are guilty of “undersharing” and that until more of us are willing to present the unpolished, not always pretty truth of our own experiences with motherhood judgment will continue to trump support and we will all be diminished by it.

Loved it...loved it...loved it. So honest and real. I loved Waldman's honesty, willing to put herself out there to be judged. I saw myself in so many parts of her and it made me feel that perhaps I'm not such a Bad Mother after all.

I liked this book, a series of 18 chapters, each depicting an aspect of motherhood. Waldman's publicized comment that she loved her husband more than her children spurned the book. Some of the stories were truly heart-breaking, like the one about Rocketship. Although I did not always agree with or "get" Waldman's perspective, I found the book interesting, thought-provoking and sometimes funny.

A couple of excerpts that resonated with me...

On the division of household/parenting duties:

"Michael (her husband, novelist, Michael Chabon)feels no counterpoint to my feminist crisis. I am solely responsible for our finances, a job that, while many women do it, might be considered the tradtional purview of aman. Yet he doesn't find it emasculating that he hasn't paid a bill in as long as I haven't changed a lightbulb. On the contrary, he'srelieved."

On parental expectations:

"There are times as a parent when your realize that your job is not to be the parent you always imagined you'd be the parent you always wished you had. Your job is to be the parent your child needs, given the particulars of his or her own life and nature."

"The point of a life, any life, is to figure out what you are good at, and what makes you happy, and, if you are very fortunate, spend your life doing those things."

A couple of excerpts that resonated with me...

On the division of household/parenting duties:

"Michael (her husband, novelist, Michael Chabon)feels no counterpoint to my feminist crisis. I am solely responsible for our finances, a job that, while many women do it, might be considered the tradtional purview of aman. Yet he doesn't find it emasculating that he hasn't paid a bill in as long as I haven't changed a lightbulb. On the contrary, he'srelieved."

On parental expectations:

"There are times as a parent when your realize that your job is not to be the parent you always imagined you'd be the parent you always wished you had. Your job is to be the parent your child needs, given the particulars of his or her own life and nature."

"The point of a life, any life, is to figure out what you are good at, and what makes you happy, and, if you are very fortunate, spend your life doing those things."

Bad mother, indeed. She bares it all, so I give her kudos for that. Some parts made me cringe, including the fact that she seems to love her husband more than she does her children. But the books makes you thin, which speaks for itself.