Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Mi maestro me recomendó este libro y comprendo por qué. Cioran despliega en esta colección de aforismos una cartografía del desencanto que resulta, paradójicamente, fascinante. Me parece que su pesimismo es el resultado de una observación despiadada de la realidad humana. La maestría del rumano radica en su capacidad para articular el hastío existencial sin caer en la autocomplacencia nihilista. Sus reflexiones sobre la temporalidad revelan una lucidez implacable que pocas veces he encontrado en la literatura filosófica contemporánea.

challenging

dark

reflective

tense

slow-paced

emotional

mysterious

reflective

medium-paced

challenging

dark

reflective

tense

slow-paced

criminally underrated. hard to come by in the physical form- if you can get your hands on this, do so expeditiously.

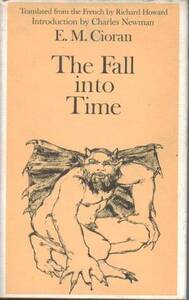

Cioran never fails to dazzle. His ruminations on humankind's hopeless condition take the shape of frenetic essays here, rather than his usual aphoristic style. It is a shame that this book has failed to be republished since its original printing. Physical copies of this work are scarce – I myself was gifted it, for which I am grateful, but it came at a cost of $90.

This work does contain an at-times frustrating mystery, which the reader must decipher as to what exactly Cioran is getting at. While this sometimes occurs with his work, it feels rather odd and rambling. My rating was somewhere between four and five but given my love for Emil and for the extravagance this book often wields, I've rounded up.

This work does contain an at-times frustrating mystery, which the reader must decipher as to what exactly Cioran is getting at. While this sometimes occurs with his work, it feels rather odd and rambling. My rating was somewhere between four and five but given my love for Emil and for the extravagance this book often wields, I've rounded up.

Nu-i bine pentru om să-şi amintească în fiecare clipă că este om. E rău fie şi numai să se aplece asupră-şi; dar e şi mai rău să se aplece asupra speciei cu zelul unui obsedat, dând astfel mizeriilor arbitrare ale introspecţiei un fundament obiectiv şi o justificare filosofică. Atâta vreme cât îţi macini propriul eu, poţi crede că cedezi unui capriciu; dar de îndată ce toate eurile devin centrul unei interminabile ruminaţii, regăseşti pe o cale ocolită neajunsurile generalizate ale propriei condiţii, propriul accident înălţat la rangul de normă, de caz universal.

Percepem mai întâi anomalia faptului brut de a exista şi abia după aceea pe cea a situaţiei noastre specifice: uimirea de a fi precede uimirea de a fi om. Totuşi, caracterul insolit al acestei stări ar trebui să constituie datul primordial al perplexităţilor noastre: e mai puţin firesc să fii om decât să fii pur şi simplu. Simţim asta instinctiv; de unde şi voluptatea ce ne cuprinde de fiecare dată când ne întoarcem faţa de la noi înşine pentru a ne cufunda în somnul preafericit al obiectelor. Nu suntem cu adevărat noi înşine decât atunci când, faţă în faţă cu sinele, nu coincidem cu nimic, nici măcar cu singularitatea noastră.

Blestemul ce ne copleşeşte apăsa şi asupra primului nostru strămoş, cu mult înainte ca acesta să fi privit către copacul cunoaşterii. Nemulţumit de sine, el era încă şi mai nemulţumit de Dumnezeu, pe care-l invidia în mod inconştient; a devenit conştient de asta datorită bunelor oficii ale ispititorului, auxiliar mai curând decât autor al ruinei sale. Înainte trăia cu presimţirea cunoaşterii, cu o ştiinţă ce se ignora pe sine, într-o falsă inocenţă, propice înfloririi geloziei, viciu zămislit de frecventarea unuia mai norocos decât sine; or, strămoşul nostru îl avea în preajmă pe Dumnezeu, pândindu-l şi fiind pândit de el. Asta nu putea duce la nimic bun.

„Din toţi pomii din rai poţi să mănânci, iar din pomul cunoştinţei binelui şi răului să nu mănânci, căci în ziua în care vei mânca din el, vei muri negreşit”.

Percepem mai întâi anomalia faptului brut de a exista şi abia după aceea pe cea a situaţiei noastre specifice: uimirea de a fi precede uimirea de a fi om. Totuşi, caracterul insolit al acestei stări ar trebui să constituie datul primordial al perplexităţilor noastre: e mai puţin firesc să fii om decât să fii pur şi simplu. Simţim asta instinctiv; de unde şi voluptatea ce ne cuprinde de fiecare dată când ne întoarcem faţa de la noi înşine pentru a ne cufunda în somnul preafericit al obiectelor. Nu suntem cu adevărat noi înşine decât atunci când, faţă în faţă cu sinele, nu coincidem cu nimic, nici măcar cu singularitatea noastră.

Blestemul ce ne copleşeşte apăsa şi asupra primului nostru strămoş, cu mult înainte ca acesta să fi privit către copacul cunoaşterii. Nemulţumit de sine, el era încă şi mai nemulţumit de Dumnezeu, pe care-l invidia în mod inconştient; a devenit conştient de asta datorită bunelor oficii ale ispititorului, auxiliar mai curând decât autor al ruinei sale. Înainte trăia cu presimţirea cunoaşterii, cu o ştiinţă ce se ignora pe sine, într-o falsă inocenţă, propice înfloririi geloziei, viciu zămislit de frecventarea unuia mai norocos decât sine; or, strămoşul nostru îl avea în preajmă pe Dumnezeu, pândindu-l şi fiind pândit de el. Asta nu putea duce la nimic bun.

„Din toţi pomii din rai poţi să mănânci, iar din pomul cunoştinţei binelui şi răului să nu mănânci, căci în ziua în care vei mânca din el, vei muri negreşit”.