Take a photo of a barcode or cover

informative

medium-paced

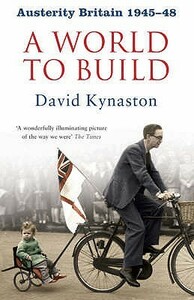

Austerity Britain - a World to Build is the first volume - strictly the first half volume - of David Kynaston's history of post WW2 Britain , beginning on VE Day and planned to end in 1979. This volume covers the immediate post war years 1945-1948.

The choice of the 1979 end date for Kynaston's projected series - he is currently up to 1962 - marks the election of the Thatcher government who proceeded to dismantle much of the post WW2 economic and social settlement that was introduced by the newly elected Labour Government from 1945. And while Kynaston generally avoids offering his personal views, one gets the impression that he feels that this dismantlement was longer overdue.

Kynaston also seems oddly infatuated with Evan Durbin, who he describes as 'the Labour Party's most interesting thinker of the 1940s and arguably of the twentieth century'. Durbin was in fact a relatively obscure right-of-centre Labour figure, albeit one of the party's young rising stars alongside Wilson, Gaitskell, Crossman etc. He died in a swimming accident in 1948 (just after the end of this book) and one gets the impression Kynaston feels that had he survived he may have led the Labour party - and the country - in a very different direction.

The 1945 Labour government is often discredited by revisionists on both the left and the right of politics - and Kynaston does a good job in demolishing certain myths.

From the right's perspective, he points out that a Tory government would have done much the same with the creation of a welfare state - and that as early as 1947 the party had accepted - publicly if not privately - many of Labour's economic reforms (nationalisation of. BofE, coal, rail, keynesian deficit finance, workers right). Hayek's road to serfdom - the bible for the Thatcherites - may have been written in 1944 but took over 20 years to become part of mainstream thinking.

And from the left, the 1945 government is often regarded as a wasted opportunity to implement full socialism. Kynaston shows that from outset the instincts of Labour were for top-down planning not giving power to workers (Kynaston makes the interesting observation that the 1945 Labour landslide actually return a lower proportion of workers to parliament as the new cadre of MPs was dominated by professionals such as economists), for Keynesian demand management rather than full blown state control (here he credits Durbin's influence), and that any attempt at neutrality between the Soviet & US blocs was undermined by the Soviet's actions in Czechoslovakia in 1948 as well as the simple economic realities of the UK's dependence on the US.

Kynaston's tale relies heavily on contemporary records for his account - diary entries but also the fascinating aural observations recorded by the Mass Observation - a body created in founded in 1937 by a group of people, who aimed to create an 'anthropology of ourselves' and who recruited a team of observers and a panel of volunteer writers to study the everyday lives of ordinary people in Britain (taken from http://www.massobs.org.uk/a_brief_history.htm)

This gives a real sense of immediacy to his history and he is thereby able to challenge many retrospective accounts, but it does make for a disjointed read at times, with a succession of anecdotes linked by forced segues (a description of radio programs and tales from a political dinner are linked by the pointless "it is unlikely that there were any listeners amongst those present that evening at the dinner party given by Hugh Dalton). And at times there is simply too much detail on the observees ("noted Alice (known to all as Judy) Haines, a youngish married woman living in Chingford, with a firm underlining in her diary")

Kynaston documents well the return to normality post VE day - starting with the symbolic return of the weather forecast (presumably suspended during the War in case it gave information to the enemy). But the overall mood is somber - even on VE day itself, with the exception of the iconic celebrations in central London, "usually crowds were too thin and too few to inspire much feeling." (another Mass Observation recording).

And "over the next few months there began to grow a pervasive sense of disenchantment that the fruits of peace were proving so unbountiful" (even if fruits such as bananas were tasted once more - my own mother, born in the mid 1930s - remembers her first taste). As a contemporary observer noted at the end of 1945: "housing, food, clothing, fuel, beer, tobacco - all the ordinary comforts of life that we'd taken for granted before the war and naturally expected to become more plentiful again when it ended, became instead more and more scarce". Indeed one suspects - although Kynaston doesn't make the point - that Labour's considerable achievements in building a welfare state, and rebuilding Britain, were rather overshadowed by the massive fiscal hole that the country found itself in.

The book ends on the day the new NHS comes into being, but also with the arrival of Windrush and the early stirrings of the immigration issue that dominates politics today. On that topic, this is a good a place as any for me to add in a wonderful quote from Joseph Carens, the Ethics of Immigration:

The choice of the 1979 end date for Kynaston's projected series - he is currently up to 1962 - marks the election of the Thatcher government who proceeded to dismantle much of the post WW2 economic and social settlement that was introduced by the newly elected Labour Government from 1945. And while Kynaston generally avoids offering his personal views, one gets the impression that he feels that this dismantlement was longer overdue.

Kynaston also seems oddly infatuated with Evan Durbin, who he describes as 'the Labour Party's most interesting thinker of the 1940s and arguably of the twentieth century'. Durbin was in fact a relatively obscure right-of-centre Labour figure, albeit one of the party's young rising stars alongside Wilson, Gaitskell, Crossman etc. He died in a swimming accident in 1948 (just after the end of this book) and one gets the impression Kynaston feels that had he survived he may have led the Labour party - and the country - in a very different direction.

The 1945 Labour government is often discredited by revisionists on both the left and the right of politics - and Kynaston does a good job in demolishing certain myths.

From the right's perspective, he points out that a Tory government would have done much the same with the creation of a welfare state - and that as early as 1947 the party had accepted - publicly if not privately - many of Labour's economic reforms (nationalisation of. BofE, coal, rail, keynesian deficit finance, workers right). Hayek's road to serfdom - the bible for the Thatcherites - may have been written in 1944 but took over 20 years to become part of mainstream thinking.

And from the left, the 1945 government is often regarded as a wasted opportunity to implement full socialism. Kynaston shows that from outset the instincts of Labour were for top-down planning not giving power to workers (Kynaston makes the interesting observation that the 1945 Labour landslide actually return a lower proportion of workers to parliament as the new cadre of MPs was dominated by professionals such as economists), for Keynesian demand management rather than full blown state control (here he credits Durbin's influence), and that any attempt at neutrality between the Soviet & US blocs was undermined by the Soviet's actions in Czechoslovakia in 1948 as well as the simple economic realities of the UK's dependence on the US.

Kynaston's tale relies heavily on contemporary records for his account - diary entries but also the fascinating aural observations recorded by the Mass Observation - a body created in founded in 1937 by a group of people, who aimed to create an 'anthropology of ourselves' and who recruited a team of observers and a panel of volunteer writers to study the everyday lives of ordinary people in Britain (taken from http://www.massobs.org.uk/a_brief_history.htm)

This gives a real sense of immediacy to his history and he is thereby able to challenge many retrospective accounts, but it does make for a disjointed read at times, with a succession of anecdotes linked by forced segues (a description of radio programs and tales from a political dinner are linked by the pointless "it is unlikely that there were any listeners amongst those present that evening at the dinner party given by Hugh Dalton). And at times there is simply too much detail on the observees ("noted Alice (known to all as Judy) Haines, a youngish married woman living in Chingford, with a firm underlining in her diary")

Kynaston documents well the return to normality post VE day - starting with the symbolic return of the weather forecast (presumably suspended during the War in case it gave information to the enemy). But the overall mood is somber - even on VE day itself, with the exception of the iconic celebrations in central London, "usually crowds were too thin and too few to inspire much feeling." (another Mass Observation recording).

And "over the next few months there began to grow a pervasive sense of disenchantment that the fruits of peace were proving so unbountiful" (even if fruits such as bananas were tasted once more - my own mother, born in the mid 1930s - remembers her first taste). As a contemporary observer noted at the end of 1945: "housing, food, clothing, fuel, beer, tobacco - all the ordinary comforts of life that we'd taken for granted before the war and naturally expected to become more plentiful again when it ended, became instead more and more scarce". Indeed one suspects - although Kynaston doesn't make the point - that Labour's considerable achievements in building a welfare state, and rebuilding Britain, were rather overshadowed by the massive fiscal hole that the country found itself in.

The book ends on the day the new NHS comes into being, but also with the arrival of Windrush and the early stirrings of the immigration issue that dominates politics today. On that topic, this is a good a place as any for me to add in a wonderful quote from Joseph Carens, the Ethics of Immigration:

Citizen in Western democracies is the modern equivalent of feudal class privilege – an inherited status that greatly enhances one’s life chances. Like feudal birthright privileges, contemporary social arrangements not to grant great advantages on the basis of birth but also entrench these advantages by legally restricting mobility, making it extremely difficult for those born into a socially disadvantaged position to overcome that disadvantage, no matter how talented they are or how hard they workOverall - a worthwhile read. But the acid test - will I eagerly read the next volume in the series? - no I won't. Generally, Kynaston may be a fine historian but he is no prose stylist and as a reader mostly of literary fiction, I found the writing turgid at times: that being said Kynaston is to be commended for avoiding the trap of exposition via footnotes (which he confines simply to source references).