Take a photo of a barcode or cover

informative

reflective

medium-paced

I did not enjoy all of this, nor did I fully understand all of this (!) but the chapter on evolution and the chapter on genetics and ethics were fascinating.

“One empirical problem in Darwinism’s focus on the competitive survival of individuals (...) has consistently been how to explain altruism (...)” p. 112

What a fascinating thought.

“One empirical problem in Darwinism’s focus on the competitive survival of individuals (...) has consistently been how to explain altruism (...)” p. 112

What a fascinating thought.

hopeful

informative

inspiring

slow-paced

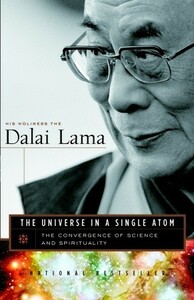

So happy to find this book in the Little Free Library box in my neighborhood. It goes along with the quantum physics books I've been reading this year and delves deeper into the implications of the kind of knowledge we are gaining from science. I enjoyed the awe and wonder the Dalai Lama shared with his readers. Especially interesting was the discussion at the end about genetics and manipulating genetics of fruits, vegetables, animals, and even humans and what the potential consequences are for Earth and humanity if we go too far with it.

"Because I am an internationalist at heart, one of the qualities that has moved me most about scientists is their amazing willingness to share knowledge with each other without regard for national boundaries. Even during the Cold War, when the political world was polarized to a dangerous degree, I found scientists from the Eastern and Western blocs willing to communicate in ways the politicians could not even imagine. I felt an implicit recognition in this spirit of the oneness of humanity and a liberating absence of proprietorship in matters of knowledge." pg. 3

"The implications of what science has to offer are still not wholly clear. Regardless of different personal views about science, no credible understanding of the natural world or our human existence--what I am going to call in this book a worldview--can ignore the basic insights of theories as key as evolution, relativity, and quantum mechanics. It may be that science will learn from an engagement with spirituality, especially in its interface with wider human issues, from ethics to society, but certainly some specific aspects of Buddhist thought--such as its old cosmological theories and its rudimentary physics--will have to be modified in the light of new scientific insights. I hope this book will be a contribution to the critical project of enlivening the dialogue between science and spirituality." pg. 5

"There is, however, a general assumption that ethics are relevant to only the application of science, not the actual pursuit of science. In this model the scientist as an individual and the community of scientists in general occupy a morally neutral position, with no responsibility for the fruits of what they have discovered. But many important scientific discoveries, and particularly the technological innovations they lead to, create new conditions and open up new possibilities which give rise to new ethical and spiritual challenges. We cannot simply absolve the scientific enterprise and individual scientists from responsibility for contributing to the emergence of a new reality." pg. 10-11

"The idea that something must be so because Newton or Einstein said so is simply not scientific. So an inquiry has to proceed from a state of openness with respect to the question at issue and to what the answer might be, a state of mind which I think of as healthy skepticism. This kind of openness can make individuals receptive to fresh insights and new discoveries; and when it is combined with the natural human quest for understanding, this stance can lead to a profound expanding of our horizons. Of course, this does not mean that all practitioners of science live up to this ideal. Some may indeed be caught in earlier paradigms." pg. 25

"Clearly, this paradigm [the current paradigm of what constitutes science] does not and cannot exhaust all aspects of reality, in particular the nature of human existence. In addition to the objective world of matter, which science is masterful at exploring, there exists the subjective world of feelings, emotions, thoughts, and the values and spiritual aspirations based on them. If we treat this realm as though it had no constitutive role in our understanding of reality, we lose the richness of our own existence and our understanding cannot be comprehensive. Reality, including our own existence, is so much more complex than objective scientific materialism allows." pg. 39

"There is, however, a third standpoint [in addition to the Buddhist 'realists' and 'idealists'], which is the position of the Prasangika school, a perspective held in the highest esteem by the Tibetan tradition. In this view, although the reality of the external world is not denied, it is understood to be relative. It is contingent upon our language, social conventions, and shared concepts. The notion of a pre-given, observer-independent reality is untenable. As in the new physics, matter cannot be objectively perceived or described apart from the observer--matter and mind are co-dependent." pg. 63

"And the world is made up of a network of complex interrelations. We cannot speak of the reality of a discrete entity outside the context of its range of interrelations with its environment and other phenomena, including language, concepts, and other conventions. Thus, there are no subjects without the objects by which they are defined, there are no objects without subjects to apprehend them, there are no doers without things done. There is no chair without legs, a seat, a back, wood, nails, the floor on which it rests, the walls that define the room it's in, the people who constructed it, and the individuals who agree to call it a chair and recognize it as something to sit on. Not only is the existence of things and events utterly contingent but, according to this principle, their very identities are thoroughly dependent upon others." pg. 64

"Even with all these profound scientific theories of the origin of the universe, I am left with questions, serious ones: What existed before the big bang? Where did the big bang come from? What caused it? Why has our planet evolved to support life? What is the relationship between the cosmos and the beings that have evolved within it? Scientists may dismiss these questions as nonsensical, or they may acknowledge their importance but deny that they belong to the domain of scientific inquiry. However, both these approaches will have the consequence of acknowledging definite limits to our scientific knowledge of the origin of our cosmos. I am not subject to the professional or ideological constraints of a radically materialistic worldview. And in Buddhism the universe is seen as infinite and beginningless, so I am quite happy to venture beyond the big bang and speculate about possible states of affairs before it." pg. 92-93

"In the earliest Buddhist scriptures there is an allusion to a story of human evolution, which is recounted in many of the subsequent Abhidharma texts. The story unfolds in the following manner. The Buddhist cosmos consists of three realms of existence--the desire realm, the form realm, and the formless realm--the last being progressively subtler states of existence. The desire realm is characterized by the experience of sensual desire and pain; this is the realm that we humans and animals inhabit. In contrast, the form realm is free from any manifest experience of pain and is permeated principally by an experience of bliss. Beings in this realm possess bodies composed of light. Finally, the formless realm utterly transcends all physical sensation. Existence in this realm is permeated by an abiding state of perfect equanimity, and the beings in this realm are entirely free from material embodiment. They exist only on an immaterial mental plane. Beings in the higher states of the desire realm and those in both the form and formless realms are described as celestial beings. It should be noted that these realms also fall within the first noble truth. They are not permanent, heavenly states to which we should aspire. They come with their own suffering of impermanence." pg. 107

"If twentieth-century history--with its widespread belief in social Darwinism and the many terrible effects of trying to apply eugenics that resulted from it--has anything to teach us, it is that we humans have a dangerous tendency to turn the visions we construct of ourselves into self-fulfilling prophecies. The idea of the 'survival of the fittest' has been misused to condone, and in some cases to justify, excesses of human greed and individualism and to ignore ethical models for relating to our fellow human beings in a more compassionate spirit. Thus, irrespective of our conceptions of science, given that science today occupies such an important seat of authority in human society, it is extremely important for those in the profession to be aware of their power and to appreciate their responsibility. Science must act as its own corrective to popular misconceptions and misappropriations of ideas that could have disastrous implications for the world and humanity at large." pg. 115

"The problem of describing the subjective experiences of consciousness is complex indeed. For we risk objectivizing what is essentially an internal set of experiences and excluding the necessary presence of the experiencer. We cannot remove ourselves from the equation. No scientific description of the neural mechanisms of color discrimination can make one understand what it feels like to perceive, say, the color red. We have a unique case of inquiry: the object of our study is mental, that which examines it is mental, and the very medium by which the study is undertaken is mental. The question is whether the problems posed by this situation for a scientific study of consciousness are insurmountable--are they so damaging as to throw serious doubt on the validity of the inquiry?" pg. 122

"Western philosophy and science have, on the whole, attempted to understand consciousness solely in terms of the functions of the brain. This approach effectively grounds the nature and existence of the mind in matter, in an ontologically reductionist manner. Some view the brain in terms of a computational model, comparing it to artificial intelligence; others attempt an evolutionary model for the emergence of the various aspects of consciousness. In modern neuroscience, there is a deep question about whether the mind and consciousness are any more than simply operations of the brain, whether sensations and emotions, are more than chemical reactions. To what extent does the world of subjective experience depend on the hardware and working order of the brain? It must to some significant extent, but does it do so entirely? What are the necessary and sufficient causes for the emergence of subjective mental experiences?" pg. 127

"To begin we become mindful of the body and the breath in a state of calm, and we cultivate awareness of the very subtle changes that occur in the mind and in the body during a period of practice, even between the in-breath and the out-breath. In this way, an experiential awareness arises that nothing within one's existence stays static or unchanging. As one fine-tunes this practice, one's awareness of change becomes ever more minute and dynamic. For example, one approach is to contemplate the complex web of circumstances that keep us alive, which leads to a deeper appreciation of the fragility of our continued existence. Another approach is a more graphic examination of bodily processes and functioning, particularly aging and decay. If a meditator has a deep knowledge of biology, then it is conceivable that there would be a specially rich content to his or her experience of this practice." pg. 155-156

"In general, the Tibetan epistemological tradition enumerates a sevenfold typology of mental states: direct perception, inferential cognition, subsequent cognition, correct assumption, inattentive perception, doubt, and distorted cognition. Young monks must learn the definitions of these seven mental states and their complex interrelations; the benefit of studying these states is that by knowing them one can become much more sensitive to the range and complexity of one's subjective experience. Being familiar with these states makes the study of consciousness more manageable." pg. 174

"Any new scientific breakthrough that offers commercial prospects attracts tremendous interest and investment from both the public sector and private enterprise. The amount of scientific knowledge and the range of technological possibilities are so enormous that the only limitations on what we do may be the results of insufficient imagination. It is this unprecedented acquisition of knowledge and power that places us in a critical position at this time. The higher the level of knowledge and power, the greater must be our sense of moral responsibility." pg. 188

"A profound aspect of the problem, it seems to me, lies in the question of what to do with our new knowledge. Before we knew that specific genes caused senile dementia, cancer, or even aging, we as individuals assumed we wouldn't be afflicted with these problems, but we responded when we were. But now, or at any rate very soon, genetics can tell individuals and families that they have genes which may kill or maim them in childhood, youth, or middle age. This knowledge could radically alter our definitions of health and sickness. For example, someone who is healthy at present but has a particular genetic predisposition may come to be marked as 'soon to be sick.' What should we do with such knowledge, and how do we handle it in a way that is most compassionate? Who should have access to such knowledge, given its social and personal implications in relation to insurance, employment, and relationships, as well as reproduction? Does the individual who carries such a gene have a responsibility to reveal this fact to his or her potential partner in life? These are just a few of the questions raised by such genetic research." pg. 190

"But I believe we must trust our instinctive feelings of revulsion, as these arise out of our basic humanity. Once we allow the exploitation of such hybrid semi-humans, what is to stop us from doing the same with our fellow human beings who the whims of society may deem deficient in some way? The willingness to step across such natural thresholds is what often leads humanity to the commission of horrific atrocities." pg. 192

"Particularly worrying is the manipulation of genes for the creation of children with enhanced characteristics, whether cognitive or physical. Whatever inequalities there may be between individuals in their circumstances--such as wealth, class, health, and so on--we are all born with a basic equality of our human nature, with certain potentialities; certain cognitive, emotional, and physical abilities; and the fundamental disposition--indeed the right--to seek happiness and overcome suffering. Given that genetic technology is bound to remain costly, at least for the foreseeable future, once it is allowed, for a long period it will be available only to a small segment of human society, namely the rich. Thus society will find itself translating an inequality of circumstance (that is, relative wealth) into an inequality of nature through enhanced intelligence, strength, and other faculties acquired through birth.

The ramifications of this differentiation are far-reaching--on social, political, and ethical levels. At the social level, it will reinforce--even perpetuate--our disparities, and it will make their reversal much more difficult. In political matters, it will breed a ruling elite, whose claims to power will be invocations of an intrinsic natural superiority. On the ethical level, these kinds of pseudo-nature-based differences can severely undermine our basic moral sensibilities insofar as these sensibilities are based on a mutual recognition of shared humanity. We cannot imagine how such practices could affect our very concept of what it is to be human." pg. 194

Book: from the Little Free Library on 33rd Avenue.

"Because I am an internationalist at heart, one of the qualities that has moved me most about scientists is their amazing willingness to share knowledge with each other without regard for national boundaries. Even during the Cold War, when the political world was polarized to a dangerous degree, I found scientists from the Eastern and Western blocs willing to communicate in ways the politicians could not even imagine. I felt an implicit recognition in this spirit of the oneness of humanity and a liberating absence of proprietorship in matters of knowledge." pg. 3

"The implications of what science has to offer are still not wholly clear. Regardless of different personal views about science, no credible understanding of the natural world or our human existence--what I am going to call in this book a worldview--can ignore the basic insights of theories as key as evolution, relativity, and quantum mechanics. It may be that science will learn from an engagement with spirituality, especially in its interface with wider human issues, from ethics to society, but certainly some specific aspects of Buddhist thought--such as its old cosmological theories and its rudimentary physics--will have to be modified in the light of new scientific insights. I hope this book will be a contribution to the critical project of enlivening the dialogue between science and spirituality." pg. 5

"There is, however, a general assumption that ethics are relevant to only the application of science, not the actual pursuit of science. In this model the scientist as an individual and the community of scientists in general occupy a morally neutral position, with no responsibility for the fruits of what they have discovered. But many important scientific discoveries, and particularly the technological innovations they lead to, create new conditions and open up new possibilities which give rise to new ethical and spiritual challenges. We cannot simply absolve the scientific enterprise and individual scientists from responsibility for contributing to the emergence of a new reality." pg. 10-11

"The idea that something must be so because Newton or Einstein said so is simply not scientific. So an inquiry has to proceed from a state of openness with respect to the question at issue and to what the answer might be, a state of mind which I think of as healthy skepticism. This kind of openness can make individuals receptive to fresh insights and new discoveries; and when it is combined with the natural human quest for understanding, this stance can lead to a profound expanding of our horizons. Of course, this does not mean that all practitioners of science live up to this ideal. Some may indeed be caught in earlier paradigms." pg. 25

"Clearly, this paradigm [the current paradigm of what constitutes science] does not and cannot exhaust all aspects of reality, in particular the nature of human existence. In addition to the objective world of matter, which science is masterful at exploring, there exists the subjective world of feelings, emotions, thoughts, and the values and spiritual aspirations based on them. If we treat this realm as though it had no constitutive role in our understanding of reality, we lose the richness of our own existence and our understanding cannot be comprehensive. Reality, including our own existence, is so much more complex than objective scientific materialism allows." pg. 39

"There is, however, a third standpoint [in addition to the Buddhist 'realists' and 'idealists'], which is the position of the Prasangika school, a perspective held in the highest esteem by the Tibetan tradition. In this view, although the reality of the external world is not denied, it is understood to be relative. It is contingent upon our language, social conventions, and shared concepts. The notion of a pre-given, observer-independent reality is untenable. As in the new physics, matter cannot be objectively perceived or described apart from the observer--matter and mind are co-dependent." pg. 63

"And the world is made up of a network of complex interrelations. We cannot speak of the reality of a discrete entity outside the context of its range of interrelations with its environment and other phenomena, including language, concepts, and other conventions. Thus, there are no subjects without the objects by which they are defined, there are no objects without subjects to apprehend them, there are no doers without things done. There is no chair without legs, a seat, a back, wood, nails, the floor on which it rests, the walls that define the room it's in, the people who constructed it, and the individuals who agree to call it a chair and recognize it as something to sit on. Not only is the existence of things and events utterly contingent but, according to this principle, their very identities are thoroughly dependent upon others." pg. 64

"Even with all these profound scientific theories of the origin of the universe, I am left with questions, serious ones: What existed before the big bang? Where did the big bang come from? What caused it? Why has our planet evolved to support life? What is the relationship between the cosmos and the beings that have evolved within it? Scientists may dismiss these questions as nonsensical, or they may acknowledge their importance but deny that they belong to the domain of scientific inquiry. However, both these approaches will have the consequence of acknowledging definite limits to our scientific knowledge of the origin of our cosmos. I am not subject to the professional or ideological constraints of a radically materialistic worldview. And in Buddhism the universe is seen as infinite and beginningless, so I am quite happy to venture beyond the big bang and speculate about possible states of affairs before it." pg. 92-93

"In the earliest Buddhist scriptures there is an allusion to a story of human evolution, which is recounted in many of the subsequent Abhidharma texts. The story unfolds in the following manner. The Buddhist cosmos consists of three realms of existence--the desire realm, the form realm, and the formless realm--the last being progressively subtler states of existence. The desire realm is characterized by the experience of sensual desire and pain; this is the realm that we humans and animals inhabit. In contrast, the form realm is free from any manifest experience of pain and is permeated principally by an experience of bliss. Beings in this realm possess bodies composed of light. Finally, the formless realm utterly transcends all physical sensation. Existence in this realm is permeated by an abiding state of perfect equanimity, and the beings in this realm are entirely free from material embodiment. They exist only on an immaterial mental plane. Beings in the higher states of the desire realm and those in both the form and formless realms are described as celestial beings. It should be noted that these realms also fall within the first noble truth. They are not permanent, heavenly states to which we should aspire. They come with their own suffering of impermanence." pg. 107

"If twentieth-century history--with its widespread belief in social Darwinism and the many terrible effects of trying to apply eugenics that resulted from it--has anything to teach us, it is that we humans have a dangerous tendency to turn the visions we construct of ourselves into self-fulfilling prophecies. The idea of the 'survival of the fittest' has been misused to condone, and in some cases to justify, excesses of human greed and individualism and to ignore ethical models for relating to our fellow human beings in a more compassionate spirit. Thus, irrespective of our conceptions of science, given that science today occupies such an important seat of authority in human society, it is extremely important for those in the profession to be aware of their power and to appreciate their responsibility. Science must act as its own corrective to popular misconceptions and misappropriations of ideas that could have disastrous implications for the world and humanity at large." pg. 115

"The problem of describing the subjective experiences of consciousness is complex indeed. For we risk objectivizing what is essentially an internal set of experiences and excluding the necessary presence of the experiencer. We cannot remove ourselves from the equation. No scientific description of the neural mechanisms of color discrimination can make one understand what it feels like to perceive, say, the color red. We have a unique case of inquiry: the object of our study is mental, that which examines it is mental, and the very medium by which the study is undertaken is mental. The question is whether the problems posed by this situation for a scientific study of consciousness are insurmountable--are they so damaging as to throw serious doubt on the validity of the inquiry?" pg. 122

"Western philosophy and science have, on the whole, attempted to understand consciousness solely in terms of the functions of the brain. This approach effectively grounds the nature and existence of the mind in matter, in an ontologically reductionist manner. Some view the brain in terms of a computational model, comparing it to artificial intelligence; others attempt an evolutionary model for the emergence of the various aspects of consciousness. In modern neuroscience, there is a deep question about whether the mind and consciousness are any more than simply operations of the brain, whether sensations and emotions, are more than chemical reactions. To what extent does the world of subjective experience depend on the hardware and working order of the brain? It must to some significant extent, but does it do so entirely? What are the necessary and sufficient causes for the emergence of subjective mental experiences?" pg. 127

"To begin we become mindful of the body and the breath in a state of calm, and we cultivate awareness of the very subtle changes that occur in the mind and in the body during a period of practice, even between the in-breath and the out-breath. In this way, an experiential awareness arises that nothing within one's existence stays static or unchanging. As one fine-tunes this practice, one's awareness of change becomes ever more minute and dynamic. For example, one approach is to contemplate the complex web of circumstances that keep us alive, which leads to a deeper appreciation of the fragility of our continued existence. Another approach is a more graphic examination of bodily processes and functioning, particularly aging and decay. If a meditator has a deep knowledge of biology, then it is conceivable that there would be a specially rich content to his or her experience of this practice." pg. 155-156

"In general, the Tibetan epistemological tradition enumerates a sevenfold typology of mental states: direct perception, inferential cognition, subsequent cognition, correct assumption, inattentive perception, doubt, and distorted cognition. Young monks must learn the definitions of these seven mental states and their complex interrelations; the benefit of studying these states is that by knowing them one can become much more sensitive to the range and complexity of one's subjective experience. Being familiar with these states makes the study of consciousness more manageable." pg. 174

"Any new scientific breakthrough that offers commercial prospects attracts tremendous interest and investment from both the public sector and private enterprise. The amount of scientific knowledge and the range of technological possibilities are so enormous that the only limitations on what we do may be the results of insufficient imagination. It is this unprecedented acquisition of knowledge and power that places us in a critical position at this time. The higher the level of knowledge and power, the greater must be our sense of moral responsibility." pg. 188

"A profound aspect of the problem, it seems to me, lies in the question of what to do with our new knowledge. Before we knew that specific genes caused senile dementia, cancer, or even aging, we as individuals assumed we wouldn't be afflicted with these problems, but we responded when we were. But now, or at any rate very soon, genetics can tell individuals and families that they have genes which may kill or maim them in childhood, youth, or middle age. This knowledge could radically alter our definitions of health and sickness. For example, someone who is healthy at present but has a particular genetic predisposition may come to be marked as 'soon to be sick.' What should we do with such knowledge, and how do we handle it in a way that is most compassionate? Who should have access to such knowledge, given its social and personal implications in relation to insurance, employment, and relationships, as well as reproduction? Does the individual who carries such a gene have a responsibility to reveal this fact to his or her potential partner in life? These are just a few of the questions raised by such genetic research." pg. 190

"But I believe we must trust our instinctive feelings of revulsion, as these arise out of our basic humanity. Once we allow the exploitation of such hybrid semi-humans, what is to stop us from doing the same with our fellow human beings who the whims of society may deem deficient in some way? The willingness to step across such natural thresholds is what often leads humanity to the commission of horrific atrocities." pg. 192

"Particularly worrying is the manipulation of genes for the creation of children with enhanced characteristics, whether cognitive or physical. Whatever inequalities there may be between individuals in their circumstances--such as wealth, class, health, and so on--we are all born with a basic equality of our human nature, with certain potentialities; certain cognitive, emotional, and physical abilities; and the fundamental disposition--indeed the right--to seek happiness and overcome suffering. Given that genetic technology is bound to remain costly, at least for the foreseeable future, once it is allowed, for a long period it will be available only to a small segment of human society, namely the rich. Thus society will find itself translating an inequality of circumstance (that is, relative wealth) into an inequality of nature through enhanced intelligence, strength, and other faculties acquired through birth.

The ramifications of this differentiation are far-reaching--on social, political, and ethical levels. At the social level, it will reinforce--even perpetuate--our disparities, and it will make their reversal much more difficult. In political matters, it will breed a ruling elite, whose claims to power will be invocations of an intrinsic natural superiority. On the ethical level, these kinds of pseudo-nature-based differences can severely undermine our basic moral sensibilities insofar as these sensibilities are based on a mutual recognition of shared humanity. We cannot imagine how such practices could affect our very concept of what it is to be human." pg. 194

Book: from the Little Free Library on 33rd Avenue.

I enjoyed diving into this look at the nature of science and Buddhism and how the two compare, conflict, and enhance one another. The Dali Lama has a strong grasp of modern science and I was surprised at the depth the book went to describing it. I enjoyed the back and forth as the Dali Lama described his desire to learn more, the teachers he had over the years in both science and Buddhism, and the how he learned from the collaboration at the bi-annual Mind and Life Conference he established. I also appreciated his take that where Buddhism and science diverge on their understandings of how the universe work that there are traditional Buddhist ideologies that need to be abandoned and replaced. I also appreciate his critique of science and how there are some understandings of human experience that have to be embraced as part of the scientific journey and not everything will and can be quantified in how the two intersect. I think an additional reading of this book would be massively useful and next time I'll take the physical copy to be able to easily reread sections that require it to gain a better understanding.

The Dalai Lama is the only major world religious figure to fully embrace science and rejoice in what it can teach us about ourselves, our universe and our spirits.

Wow. I was deeply impressed by the incredibly insightful and intelligent perspective of His Holiness. I was also at a loss to comprehend much of what I read. I suppose I'm reviewing based on what I felt while reading, not what I understood. It was very uplifting to learn more about the life of His Holiness. I greatly admired his desire to learn about a variety of many things and to seek knowledge in pursuit of understanding mortality and helping others. Much of this book went over my head, but what did stick was inspiration to be more grateful and to love learning.

As you might image from someone who reads physics books for fun, this book covered some mindbendingly complex stuff: the theory of relativity, quantum physics, The Big Bang, the concept of consciousness, and genetics.

For someone who has entered the Science Arena late and who gets his info from reading and conversing with the great minds of science, he has a marvelous handle on things. I think. I admit I was lost more than once. But that's ok, because while he talked a lot about science, the book was focused on the intersection of science and Buddhism.

Where science stresses 3rd person impartial observation, Buddhism stressed 1st person experiential reflection. And both methods come startlingly close to the same conclusions at times. Apart from that, The Dalai Lama says that Buddhist concern with the well-being of others can provide a tempering of the indisputably advantageous scientific advances yet do-things-because-we-can attitude. For example, genetic testing can now tell if a baby has things like Down Syndrome whilst still in the womb. If the parents aren't mentally or physically capable of parenting such a child, should they abort? The Dalai Lama says, what if you do and then science discovers a cure?

I've your interested in thinking about such things like that, by that I mean science guided by ethics, then this will be a good read. Just don 't be afraid if you get lost in certain chapters. He covers a wide array of scientific thought.

For someone who has entered the Science Arena late and who gets his info from reading and conversing with the great minds of science, he has a marvelous handle on things. I think. I admit I was lost more than once. But that's ok, because while he talked a lot about science, the book was focused on the intersection of science and Buddhism.

Where science stresses 3rd person impartial observation, Buddhism stressed 1st person experiential reflection. And both methods come startlingly close to the same conclusions at times. Apart from that, The Dalai Lama says that Buddhist concern with the well-being of others can provide a tempering of the indisputably advantageous scientific advances yet do-things-because-we-can attitude. For example, genetic testing can now tell if a baby has things like Down Syndrome whilst still in the womb. If the parents aren't mentally or physically capable of parenting such a child, should they abort? The Dalai Lama says, what if you do and then science discovers a cure?

I've your interested in thinking about such things like that, by that I mean science guided by ethics, then this will be a good read. Just don 't be afraid if you get lost in certain chapters. He covers a wide array of scientific thought.