Take a photo of a barcode or cover

Aside from the northern Michigan points of reference this book was such a waste of my precious reading time.

Just because an author is aware that it is ridiculous to make fiction in the modern world doesn't mean he has to write a character who is an author who is aware that it is ridiculous to make fiction in the modern world. It shouldn't be a surprise that this character is unlikable, or that very little happens in a plot that revolves at some level around this character's writer's block. Sorrentino can obviously write, but he shouldn't have written this book.

Sorrentino jerked off on a keyboard for three days and autocorrect turned it into this book. And Sorrentino's just so fucking clever, he got it published.

Two-thirds into the book, I hadn't really made up my mind about whether I liked it or not. The scaffolding along which the book unfolds is an intriguing little mystery: a former casino employee tips off a reporter friend about a secret casino heist. Secret because the stolen money was money already being skimmed off the top, so its theft couldn't be reported to the police. And according to the source, the guy who walked away with a cool half mil has popped back up in the area as a Native storyteller, of all things, with a thinly disguised name. Did the theft really happen? If so, is the thief really the same guy as this storyteller who tells Native fables to the kids at the local library?

I liked the mystery. The stakes weren't terribly high, perhaps, but I really wanted to know the answers to those questions.

To get those answers, though, I had to wade through a lot of what felt like literary filler. One of the storyteller's admirers--and one of the book's primary narrators--is a successful novelist who's made a mess of his life, and his ruminations are sometimes self-loathing and sometimes self-aggrandizing, but always self-centered. He hits on the reporter who's investigating the mystery, and there's a lot of unnecessary detail about their sexual relationship. In fact, her sexual escapades figure pretty heavily in the book, although they're somehow an odd mix of sordid and relatively uninteresting. It's telling that of the reporter, who is the only significant female character in the book, we know much more of her affairs and bedroom proclivities than we do of her reporting style. She seems to be motivated by two things: generically, by wanting to break a big story, and less generically, by wanting to perform fellatio on various men. It just didn't make for a very interesting character, let alone one I could invest in.

That said, the mystery really picked up in the last third of the book, and I came to wish that the author had discarded some of his literary pretentions and written a really solid crime thriller instead. It ended on a fairly high note, and my feeling by the end of the book was that it was a four-star read. Only in thinking back over the course of the experience and rereading some notes I'd taken along the way was I reminded of the parts I didn't particularly enjoy.

I received a complimentary copy of this book from the publisher in exchange for my honest review.

I liked the mystery. The stakes weren't terribly high, perhaps, but I really wanted to know the answers to those questions.

To get those answers, though, I had to wade through a lot of what felt like literary filler. One of the storyteller's admirers--and one of the book's primary narrators--is a successful novelist who's made a mess of his life, and his ruminations are sometimes self-loathing and sometimes self-aggrandizing, but always self-centered. He hits on the reporter who's investigating the mystery, and there's a lot of unnecessary detail about their sexual relationship. In fact, her sexual escapades figure pretty heavily in the book, although they're somehow an odd mix of sordid and relatively uninteresting. It's telling that of the reporter, who is the only significant female character in the book, we know much more of her affairs and bedroom proclivities than we do of her reporting style. She seems to be motivated by two things: generically, by wanting to break a big story, and less generically, by wanting to perform fellatio on various men. It just didn't make for a very interesting character, let alone one I could invest in.

That said, the mystery really picked up in the last third of the book, and I came to wish that the author had discarded some of his literary pretentions and written a really solid crime thriller instead. It ended on a fairly high note, and my feeling by the end of the book was that it was a four-star read. Only in thinking back over the course of the experience and rereading some notes I'd taken along the way was I reminded of the parts I didn't particularly enjoy.

I received a complimentary copy of this book from the publisher in exchange for my honest review.

Suspecting sanctimonius satire, I had a hard time getting into this novel. It turned out to be pretty refreshing and quite funny, when it wasn't sad and mournful that is. The mystery part of it (man disappears from casino with bag full of cash, reporter sleuths) wasn't most intriguing part. The characters (oversexed, self-pitying author, oversexed, self-destructive reporter) and their self-scrutiny interested me the most. It's a peculiar novel and I wouldn't know who to recommend it to, but I'm glad I kept going.

This book is fine, i guess. I just don’t like it when i finish a book and feel like i need to google it to find out wth happened. Also... so.many.words. Sentences that just went on and on and on. Just not for me.

The first two-thirds or so of this book was fantastic, then it seemed like the author lost interest.

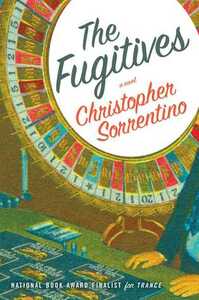

Award-winning author Christopher Sorrentino, whose writing has been compared to Don DeLillo, Hunter S Thompson and Philip Roth, brings us a story of race, identity, story-telling and truth in The Fugitives.

Sandy is a fugitive from his ex-wife and the relationships that have caused a scandal back in New York. He flees to Michigan, hoping the seclusion will help him finish his latest novel. Kat flees her clingy, needy boyfriend and an unsatisfying job, chasing a story that might propel her career into what she really wants. She’s also fleeing her past, as she seeks anonymity and abandons her cultural identity. They meet at a library, where John Salteau tells “Native Tales” to children. However, is he really who he claims to be? Or is he too a fugitive, hiding in plain sight from the local mobsters?

My first impression was overwhelmingly positive. I highlighted almost every other paragraph to quote later; Christopher Sorrentino really knows how to put a sentence together. I liked the characters and I was interested in the story of some gangster pretending to be a Chippewa Indian. It was interesting to see how the book touched on the workings of the publishing industry, concepts of identity and race (and how we create identity through the stories we tell ourselves), and the action-packed parts were exciting. However, as I read on, small flaws started to bother me.

Sorrentino’s style is very intellectual; he writes long, dense sentences that sometimes need to be unpacked a little. Sometimes a paragraph covers multiple pages and when you get to the end you’re still not sure what it was pointing you towards. This is not a quick, easy read; it requires the reader to do a bit of work, and there’s a lot of reading between the lines that must happen as well. He plays with form, sometimes to great effect. Sometimes it was a little confusing. Even with a degree in literature, and the handy built-in Kindle dictionary, I found it tricky to get the main point behind what a lot of the book was saying. I feel like this is a book the critics and literati will love, but the laymen will simply scratch their heads and feel inadequate as the point goes soaring over their heads.

However, it’s not all bad. For instance, Sorrentino does some interesting things with form, using his two narrators (one in first person, and utterly unreliable, and the other slightly more reliable third, but very selective and secretive) to tell the story. It was slightly repetitive until I realised what was going on; there were tiny contradictions pointing out the flaws in their stories, both in how they describe themselves and how they describe the world around them. Sandy frequently glosses over the truth, choosing instead the version that portrays himself in the best light, while Kat’s cynicism exaggerates the negatives and ignores many positives. It was very cunningly done; I feel like Sorrentino gleefully distracts the reader with long, dense monologues about publishing and race and identity, sucking you in as you believe everything you’re told, until, in the end, with Iain Banks-like flair, nothing has any substance or certainty. I finished the book, completely confused. But I enjoyed the ride.

Is it a flaw for a book to be too clever? Maybe. For me, I found that the most interesting part of the story got about 5% of the attention. I cared more about Salteau and his real identity, and how he went about conning people, and what happened to the missing money, and the gangsters and Becky and so on, than I did about Sandy’s narcissistic existential crises, or Kat’s bitter self-loathing and their mutual self-destruction. As interested as I am about the publishing process and the “death of print”, I skimmed most of Monte, Nables and Dylan’s monologues about them. I’m sure there are people who will appreciate the intertextuality and meta and fourth-wall breaking and so on; for me, it felt like a load of pretentious waffling, whingeing and obfuscation that took narrative time away from the real story. This book is a lot of work to understand, and I feel like I missed the main point of it. However, the words sounded good together, the characters were great, the main premise was gripping and I loved how the narration of the story became a pivotal part of the story as well.

I received this book from the publisher for free, in exchange for an honest review. You can read more of my reviews at Literogo.com.

If I arrive at the library before eleven, I’ll wait. There’s no other feeling like that of the restraint in a quiet room filled with people. Conditional unity, breached under the duress of petty bodily betrayals, farts and sneezes. The heads come up, mildly curious, then fall once more to the printed lines.

Sandy is a fugitive from his ex-wife and the relationships that have caused a scandal back in New York. He flees to Michigan, hoping the seclusion will help him finish his latest novel. Kat flees her clingy, needy boyfriend and an unsatisfying job, chasing a story that might propel her career into what she really wants. She’s also fleeing her past, as she seeks anonymity and abandons her cultural identity. They meet at a library, where John Salteau tells “Native Tales” to children. However, is he really who he claims to be? Or is he too a fugitive, hiding in plain sight from the local mobsters?

Only a very few were born to love the status quo, at least insofar as they were certain that it contained a privileged place for them. Everyone else, accommodating it in all of its arbitrary contradictions, effaced to a certain extent what they’d been branded with at birth. But Nables couldn’t erase the rubbed ebony skin, the full lips, the broad nose with the flaring nostrils, and he was even less capable of erasing the stroke of indignation connecting his every decision to a central motivation. So he messed with his staff. It was a way of actively not waiting for the chimerical story that would force the world to apologize for being itself.

My first impression was overwhelmingly positive. I highlighted almost every other paragraph to quote later; Christopher Sorrentino really knows how to put a sentence together. I liked the characters and I was interested in the story of some gangster pretending to be a Chippewa Indian. It was interesting to see how the book touched on the workings of the publishing industry, concepts of identity and race (and how we create identity through the stories we tell ourselves), and the action-packed parts were exciting. However, as I read on, small flaws started to bother me.

Oh how well she’d avoided Becky Chasse for ten years. Just didn’t want to go wherever that might lead. People bobbed up all the time, more often than you’d ever dream; she pictured a billion souls spread out across the night, each tapping the names of the lost into a search engine by the light of a single lamp. But happy reunions were for Facebook, a nice smooth interface between you and all the bad habits and ancient disharmonies. Who was waiting for you in the vast digital undertow there? Kat avoided it.

Sorrentino’s style is very intellectual; he writes long, dense sentences that sometimes need to be unpacked a little. Sometimes a paragraph covers multiple pages and when you get to the end you’re still not sure what it was pointing you towards. This is not a quick, easy read; it requires the reader to do a bit of work, and there’s a lot of reading between the lines that must happen as well. He plays with form, sometimes to great effect. Sometimes it was a little confusing. Even with a degree in literature, and the handy built-in Kindle dictionary, I found it tricky to get the main point behind what a lot of the book was saying. I feel like this is a book the critics and literati will love, but the laymen will simply scratch their heads and feel inadequate as the point goes soaring over their heads.

To erase yourself completely was commonly thought to be the most difficult of feats. Most people’s identities were important to them, something they wouldn’t shed. It was proud, it was timid, it was laudable, it was stupid. It stuck people with dumb friends and crummy marriages. Trapped them in dead towns and murderous neighborhoods. It manufactured tradition from the uninterrupted drudgery of successive generations. It transformed ignorant belief into folklore, and ignorance itself into defiance. Identity was a trap.

However, it’s not all bad. For instance, Sorrentino does some interesting things with form, using his two narrators (one in first person, and utterly unreliable, and the other slightly more reliable third, but very selective and secretive) to tell the story. It was slightly repetitive until I realised what was going on; there were tiny contradictions pointing out the flaws in their stories, both in how they describe themselves and how they describe the world around them. Sandy frequently glosses over the truth, choosing instead the version that portrays himself in the best light, while Kat’s cynicism exaggerates the negatives and ignores many positives. It was very cunningly done; I feel like Sorrentino gleefully distracts the reader with long, dense monologues about publishing and race and identity, sucking you in as you believe everything you’re told, until, in the end, with Iain Banks-like flair, nothing has any substance or certainty. I finished the book, completely confused. But I enjoyed the ride.

Your authority derived from the story you recognized to be about yourself. You adopted it, told it, then found other people who told the same story. The days of evading witnesses were over. The witnesses eliminated themselves; faded into the fabric of new jobs, new cities, new pastimes, new friends; multiple vectors diverging from a common originating point. The days of people were over. It was a vast democratic plurality of groups out there – political parties, associations, alumni, fans, account holders, veterans, employees, signatories, professions, and end users. Join and vanish. Learn the secret handshake, get the secret haircut. Try to be a person and you realized just how alone you really were. The only thing to do was to break away, shed what marked you before you were shed and disowned.

Is it a flaw for a book to be too clever? Maybe. For me, I found that the most interesting part of the story got about 5% of the attention. I cared more about Salteau and his real identity, and how he went about conning people, and what happened to the missing money, and the gangsters and Becky and so on, than I did about Sandy’s narcissistic existential crises, or Kat’s bitter self-loathing and their mutual self-destruction. As interested as I am about the publishing process and the “death of print”, I skimmed most of Monte, Nables and Dylan’s monologues about them. I’m sure there are people who will appreciate the intertextuality and meta and fourth-wall breaking and so on; for me, it felt like a load of pretentious waffling, whingeing and obfuscation that took narrative time away from the real story. This book is a lot of work to understand, and I feel like I missed the main point of it. However, the words sounded good together, the characters were great, the main premise was gripping and I loved how the narration of the story became a pivotal part of the story as well.

I received this book from the publisher for free, in exchange for an honest review. You can read more of my reviews at Literogo.com.

A formerly successful novelist, way behind on the delivery of his next manuscript, escapes the mess of his marriage, and a scandalous affair, by leaving Brooklyn for a quiet Michigan town near the locale of fondly remembered family holidays. There he wanders into the library for the regular storytelling of a Native American who delights listeners with indigenous fables. The storyteller begins the novel so you might imagine he features prominently, as he does, and you might also imagine there are fable-like lessons to be learned, which there may be. Enter a reservation expat, now a Chicago journalist, who has received a tip that the storyteller may not be who he pretends to be, and who may be the link to a gambling casino theft. Prepare to read a lot of pages before a crime is revealed, but it’s less important than the personal misdemeanors of each of these characters. Of course the novelist and the journalist are drawn to each other. Of course an elegant wise guy takes note of the journalists exploration and intercedes. Add one angry husband, a few angry exes, Indian reservation police, a lot meaningless sex and a crazy funny literary agent on the rampage, and you have one helluva read. I couldn’t put it down. I laughed, I cringed. I pondered why people forget what they’ve learned. I thought about how deeply failure and grief impact the psyche. I also wondered whether any of these characters would come out in a better place. Christopher Sorrentino is skilled and smart and he wants us to really know our characters as we watch them stumble into each other, and into their own way, and as they become part of the mystery they seek to unravel. Acompelling novel of cultural conflict and personal compulsions.