Take a photo of a barcode or cover

70 reviews for:

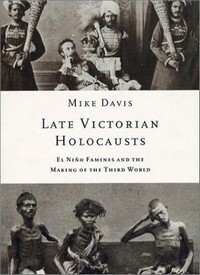

Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World

Mike Davis

70 reviews for:

Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World

Mike Davis

challenging

dark

informative

sad

medium-paced

informative

medium-paced

started off strong but I found account and assessment Chinese political history eyebrow raising which was enough to entire the entire book for me in addition to what is painfully scant sections of Brazil.

informative

medium-paced

Uma história que nunca havia lido em outros livros, pelo que lembro, pelo menos. Mike Davis conta um pouco do que aconteceu no terceiro mundo (pelo menos na época) enquanto a colonização inglesa avançava. O livro traz uma discussão grande sobre o que acontece quando Governos e economia se fortalecendo entram em conflito com subsistência e quem não é interessante para economia ou votos. Com direito a uma passagem pelo Nordeste brasileiro no fim do século XIX.

Estou bem acostumado com a narrativa do capitalismo trazendo a prosperidade (de [b:The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow's World|34959327|The Wizard and the Prophet Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow's World|Charles C. Mann|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1498830376s/34959327.jpg|56233353] a[b:O otimista racional: Por que o mundo melhora|40885354|O otimista racional Por que o mundo melhora|Matt Ridley|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1532118750s/40885354.jpg|63716393]), mas nunca tinha lido sobre o que pode dar errado. Quando o capitalismo traz fome. Até ver o que acontece quando a Inglaterra estende vias de comércio e linhas de trem para a Índia e ingleses podem pagar mais pelo trigo do que os indianos. Só ingleses comem e a Índia passar por uma Fome enorme.

Estou bem acostumado com a narrativa do capitalismo trazendo a prosperidade (de [b:The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow's World|34959327|The Wizard and the Prophet Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow's World|Charles C. Mann|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1498830376s/34959327.jpg|56233353] a[b:O otimista racional: Por que o mundo melhora|40885354|O otimista racional Por que o mundo melhora|Matt Ridley|https://images.gr-assets.com/books/1532118750s/40885354.jpg|63716393]), mas nunca tinha lido sobre o que pode dar errado. Quando o capitalismo traz fome. Até ver o que acontece quando a Inglaterra estende vias de comércio e linhas de trem para a Índia e ingleses podem pagar mais pelo trigo do que os indianos. Só ingleses comem e a Índia passar por uma Fome enorme.

challenging

informative

sad

slow-paced

informative

medium-paced

informative

fast-paced

Well, that's a thorough book. Could have been slightly shortened for my taste. But at least it's thorough. Only weird thing: after over 400 pages, it just ends. No conlusion, no outlook. After such an in-depth analysis, this end came unexpected. But Davis' style is incredibly readable, given the topic's complexity.

informative

reflective

slow-paced

If the history of British rule in India were to be condensed into a single fact, it is this: there was no increase in India's per capita income from 1757 to 1947.

This is a harrowing tome, one dense with statistics and cutting with testimonial. The first section details the effects of drought and famine on India, China and Brazil in the late 19C. Their are accounts from notables of the time. The second section examines the science of El Nino. The final section surveys the global economies of the period, citing all the requisite authorities, the conclusion is despairing. Economic and technological advances clearly set the table for despair and calamity. Racism and corruption maximized the effect.

This is a harrowing tome, one dense with statistics and cutting with testimonial. The first section details the effects of drought and famine on India, China and Brazil in the late 19C. Their are accounts from notables of the time. The second section examines the science of El Nino. The final section surveys the global economies of the period, citing all the requisite authorities, the conclusion is despairing. Economic and technological advances clearly set the table for despair and calamity. Racism and corruption maximized the effect.