Scan barcode

booktwitcher23's review

challenging

reflective

slow-paced

- Plot- or character-driven? N/A

- Strong character development? N/A

- Loveable characters? N/A

- Diverse cast of characters? N/A

- Flaws of characters a main focus? N/A

2.0

jimmylorunning's review

4.0

Five of these essays are about writers (Johann Peter Hebel, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Eduard Morike, Gottfried Keller, and Robert Walser) and the last is about a painter (Jan Peter Tripp). What immediately sets this collection apart from other collections of literary criticism is Sebald's unique voice, his slow sobering rhythms, learned yet personable, full of humanity and curiosity, sweeping in its scope from political to personal. Criticism that focuses on the biography of the writer usually turns me off, but here Sebald blends these biographical elements with personal recollections, historical context, and upclose examinations of the writing itself so that all these elements become inextricably entangled when considering the work/writer. This is as it should be. This is the perfect type of criticism, and probably shouldn't even be called criticism, for it simply feels like you are talking to Sebald about his literary heroes in a conversation that mirrors many of his books, full of asides and observations and stories. I was led to think about crystals when reading about Morike--curiously enough, a while ago I read an essay about the recurrence of crystals in Sebald's own writing (a series of essays by Caspar Mao that is no longer on the internet, sadly). While reading about Keller, I was led to think about how hoarders are in their own small way rebelling against capitalism, putting value on the value-less and therefore keeping money out of circulation... perhaps that is why we as a society publicly mock hoarders on television--many psychological conditions deserve our empathy, but oddly we don't feel the need to extend this to hoarders. In the writers he chose, one can detect the same themes that drew Sebald to write his own books, and in the shadow of this personal literary history can be drawn Sebald's own vague melancholy, the lingering curse of always being outside, of exile and alienation in an unforgiving time. In his own "prose fictions", Sebald --perhaps wisely-- does not touch on the historical and political quite as explicitly as he does here, when talking about other writers. Nonetheless, that preoccupation with history's stain permeates all his books, so it is quite refreshing to see him open up.

buddhafish's review against another edition

4.0

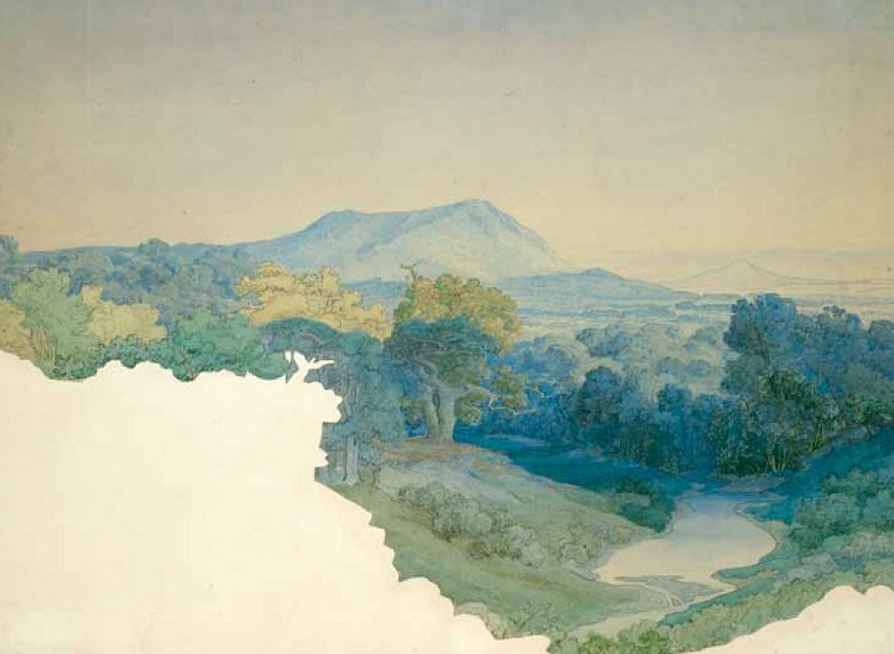

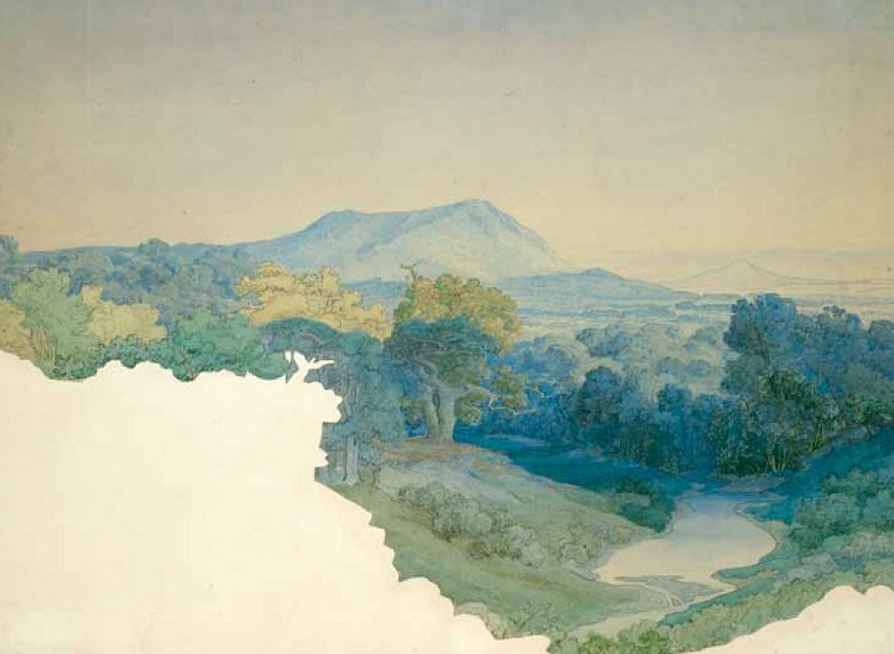

72nd book of 2021. No artist for this review, instead pictures used from the text itself.

4.5. (Dropped to 4 when comparing to Sebald's novels.) As I've read all of Sebald's novels (and consider him one of my all-time favourite writers and inspirations), I'm now pushing into his other areas of written work: poetry and essays. A Place in the Country is comprised of six essays on various writers and finally an artist: Johann Peter Hebel, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Eduard Mörike, Gottfried Keller, Robert Walser, and Jan Peter Tripp. Sebald states in his Foreword,

He touches on the important thing about these essays right here: like his fiction, these essays are multifaceted looks at their subjects, including snatches of the autobiographical from Sebald, biographies of the subjects, from general musings, appreciations, less literary criticism and more literary (and personal) appreciation. And he ends his Foreword by saying, with all the beauty that Sebald says almost anything:

Despite being only really familiar with Rosseau, the essays were illuminating for me. Rosseau's essay is, too, perhaps, the most realised of the collection. I may believe this because it is the heaviest with Sebald's own presence. It opens as such.

(And as we discuss Sebald discussing other writers let us take a moment to discuss Sebald himself here. This paragraph is comprised of just three Sebaldian sentences of great length and grace; his prose is effortless, wandering, that builds itself, ripple-by-ripple, until its conclusion breaks and washes us down. Even here in his essays, he presents himself as a master of prose.)

And before he discusses Rosseau's work he describes the room he took: The room I took at the hotel looked out on the south side of the building, directly adjacent to the two rooms which Jean-Jacques Rosseau occupied when, in September 1765, exactly 200 years before my first sight of the island from the top of the Schattenrain, he found refuge here...; and Sebald once again expresses, firmly but subtly, a general contempt for the modern world he inhabits,

S. once told me that he had begun writing a biography on the writer A.E. Coppard (whom he oddly resembles in certain photographs, though was surprised to find people telling him this); he told me of the stories he had found throughout his research, playing cricket with Robert Graves, or breaking into Yeats' garden. The project soured though, he told me, because the family were very protective of Coppard's image and had previously attacked earlier attempts at rooting about in his life. Though I expressed disappointment, and was disappointed to see his evident excitement extinguished, he told me that visiting those places that Coppard had been had instilled in him a strange feeling. He told me not to underestimate the power of place, and the place where those that have inspired us have been. "Literary journeys", he called them, and urged me there and then to take as many as I can. I believe, he said to me, that there is a certain power there, somehow, left by them, which can find its way into us.

And so it's no surprise that in a similar vein Sebald writes,

The essays retain some of the sadness always found in Sebald's prose. Some of his subjects, such as Mörike make for sad subjects.

Keller is another beautiful, sad and slightly disturbing essay. There are images imbedded in the text of his incessant writing of a woman's name, plagued by unrequited love, Betty Betty Betty, BBettytybetti, bettibettibetti, Bettybittebetti [Bettypleasebetti] is scrawled and doodled there in every calligraphic permutation imaginable. It is reminiscent of the moment Humbert Humbert asks the finder of his notebook to repeat the name Lolita for the entire page.

The Robert Walser is perhaps the best essay in the collection along with Rosseau. In it, Sebald draws comparisons between Walser and Sebald's own grandfather, of dates that seem to correspond within their lives, of other strange affinities. (On all these paths Walser has been my constant companion. I only need to look up for a moment in my daily work to see him standing somewhere a little apart, the unmistakable figure of the solitary walker just pausing to take in the surroundings.)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/G5NMCIQ2AZCY3BU4ROFMQ6ZBFQ.jpg)

This is not simply literary criticism but the understanding of the strange ways that writers, for sometimes reasons outside of our understanding, haunt us. Walser is there haunting Sebald as Nabokov haunts each of the four parts in his novel The Emigrants. It makes me wonder if there is a thread that could be found between all writers, haunting one another in some way. I remember reading recently about Kawabata's suicide (or not suicide, no one knows) following Yukio Mishima's death; and how, Kawabata, apparently, according to his biographer, had recurring nightmares about him, for two or three hundred nights in a row, and was "incessantly haunted by the specter of Mishima". This collection of essays is really a reflection on the spectres in Sebald's life. And in turn he has become a spectre in my own.

4.5. (Dropped to 4 when comparing to Sebald's novels.) As I've read all of Sebald's novels (and consider him one of my all-time favourite writers and inspirations), I'm now pushing into his other areas of written work: poetry and essays. A Place in the Country is comprised of six essays on various writers and finally an artist: Johann Peter Hebel, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Eduard Mörike, Gottfried Keller, Robert Walser, and Jan Peter Tripp. Sebald states in his Foreword,

And so it is a reader, first and foremost, that I wish to pay tribute to these colleagues who have gone before me, in the form of these extended marginal notes and glosses, which do not otherwise have any particular claim to make.

He touches on the important thing about these essays right here: like his fiction, these essays are multifaceted looks at their subjects, including snatches of the autobiographical from Sebald, biographies of the subjects, from general musings, appreciations, less literary criticism and more literary (and personal) appreciation. And he ends his Foreword by saying, with all the beauty that Sebald says almost anything:

I have learned how it is essential to gaze far beneath the surface, that art is nothing without patient handiwork, and that there are many difficulties to be reckoned with in the recollection of things.

Despite being only really familiar with Rosseau, the essays were illuminating for me. Rosseau's essay is, too, perhaps, the most realised of the collection. I may believe this because it is the heaviest with Sebald's own presence. It opens as such.

At the end of September 1965, having moved to the French-speaking part of Switzerland to continue my studies, a few days before the beginning of the semester I took a trip to the nearby Seeland, where, starting from Ins, I climbed up the so-called Schattenrain. It was a hazy sort of day, and I remember how, on reaching the edge of the small wood covering the slope, I paused to look back down at the path I had come by, at the plain stretching away to the north criss-crossed by the straight lines of canals, with the hills shrouded in mist beyond; and how, when I emerged once more into the fields above the village of Lüscherz, I saw spread out below me the Lac de Bienne, and sat there for an hour or more lost in thought at the sight, resolving that at the earliest opportunity I would cross over to the island in the lake which, on that autumn day, was flooded with a trembling pale light. As so often happens in life, however, it took another thirty-one years before this plan could be realized and I was finally able, in the early summer of 1996, in the company of an exceedingly obliging host who lived high above the steep shores of the lake and who habitually wore a kind of captain's cap, smoked Indian bidis and seldom spoke, to make the journey across the lake from the city of Bienne to the island of Saint-Pierre, formed during the last ice age by the retreating Rhône glacier into the shape of a whale's back—or so it is generally said.

(And as we discuss Sebald discussing other writers let us take a moment to discuss Sebald himself here. This paragraph is comprised of just three Sebaldian sentences of great length and grace; his prose is effortless, wandering, that builds itself, ripple-by-ripple, until its conclusion breaks and washes us down. Even here in his essays, he presents himself as a master of prose.)

And before he discusses Rosseau's work he describes the room he took: The room I took at the hotel looked out on the south side of the building, directly adjacent to the two rooms which Jean-Jacques Rosseau occupied when, in September 1765, exactly 200 years before my first sight of the island from the top of the Schattenrain, he found refuge here...; and Sebald once again expresses, firmly but subtly, a general contempt for the modern world he inhabits,

At any rate, in the few days I spent on the island—during which time I passed not a few hours sitting by the window in the Rosseau room—among the tourists who come over to the island on a day trip for a stroll or a bite to eat, only two strayed into this room with its sparse furnishings—a settee, a bed, a table and a chair—and even those two, evidently disappointed at how little there was to see, soon left again. Not one of them bent down to look at the glass display case to try to decipher Rosseau's handwriting, nor noticed the way that the bleached deal floorboards, almost two feet wide, are so worn down in the middle of the room as to form a shallow depression, nor that in places the knots in the wood protrude by almost an inch. No one ran a hand over the stone basin worn smooth by age in the antechamber, or noticed the smell of soot which still lingers in the fireplace, nor paused to look out the window with its view across the orchard and a meadow to the island's southern shore.

S. once told me that he had begun writing a biography on the writer A.E. Coppard (whom he oddly resembles in certain photographs, though was surprised to find people telling him this); he told me of the stories he had found throughout his research, playing cricket with Robert Graves, or breaking into Yeats' garden. The project soured though, he told me, because the family were very protective of Coppard's image and had previously attacked earlier attempts at rooting about in his life. Though I expressed disappointment, and was disappointed to see his evident excitement extinguished, he told me that visiting those places that Coppard had been had instilled in him a strange feeling. He told me not to underestimate the power of place, and the place where those that have inspired us have been. "Literary journeys", he called them, and urged me there and then to take as many as I can. I believe, he said to me, that there is a certain power there, somehow, left by them, which can find its way into us.

And so it's no surprise that in a similar vein Sebald writes,

For me, though, as I sat in Rosseau's room, it was as if I had been transported back to an earlier age, an illusion I could indulge in all the more readily inasmuch as the island still retained that same quality of silence, undisturbed by even the most distant sound of a motor vehicle, as was still to be found everywhere in the world a century or two ago.

The essays retain some of the sadness always found in Sebald's prose. Some of his subjects, such as Mörike make for sad subjects.

And so we see Mörike at the last sitting in the garden surrounded by his wife's relations on a hot summer's day, the only one with a book in his hand, and in the end not very content in his role as a poet, from which he—unlike his clerical calling—can no longer retire. Still he has to torment himself with his novel and other such literary matters. But for years now the work has not really been going anywhere. The painter Friedrich Pecht, in a reminiscence about this time, relates how on several occasions he observed Mörike noting things down which came into his head on speecial scraps and pieces of paper, only soon afterwards to take these notes and 'tear them up into little pieces and bury them in the pockets of his dressing-gown.'

Keller is another beautiful, sad and slightly disturbing essay. There are images imbedded in the text of his incessant writing of a woman's name, plagued by unrequited love, Betty Betty Betty, BBettytybetti, bettibettibetti, Bettybittebetti [Bettypleasebetti] is scrawled and doodled there in every calligraphic permutation imaginable. It is reminiscent of the moment Humbert Humbert asks the finder of his notebook to repeat the name Lolita for the entire page.

The Robert Walser is perhaps the best essay in the collection along with Rosseau. In it, Sebald draws comparisons between Walser and Sebald's own grandfather, of dates that seem to correspond within their lives, of other strange affinities. (On all these paths Walser has been my constant companion. I only need to look up for a moment in my daily work to see him standing somewhere a little apart, the unmistakable figure of the solitary walker just pausing to take in the surroundings.)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/G5NMCIQ2AZCY3BU4ROFMQ6ZBFQ.jpg)

This is not simply literary criticism but the understanding of the strange ways that writers, for sometimes reasons outside of our understanding, haunt us. Walser is there haunting Sebald as Nabokov haunts each of the four parts in his novel The Emigrants. It makes me wonder if there is a thread that could be found between all writers, haunting one another in some way. I remember reading recently about Kawabata's suicide (or not suicide, no one knows) following Yukio Mishima's death; and how, Kawabata, apparently, according to his biographer, had recurring nightmares about him, for two or three hundred nights in a row, and was "incessantly haunted by the specter of Mishima". This collection of essays is really a reflection on the spectres in Sebald's life. And in turn he has become a spectre in my own.

maxmischa83's review against another edition

3.0

"Walser moet op dat tijdstip hebben gehoopt dat hij zich al schrijvend, door iets heel zwaars te veranderen in iets bijna gewichtloos, zou kunnen onttrekken aan de schaduwen die vanaf het begin over zijn leven lagen en waarvan hij al vroeg voorziet dat ze onstuitbaar langer worden. Zijn ideaal was het overwinnen van de zwaartekracht."

Sebald schetst in 6 hoofdstukken of essays het leven en werk van mij 5 onbekende schrijvers en 1 schilder. Net zoals in zijn meesterwerk 'Austerlitz' vermengt hij veel weetjes en citaten over de auteurs met kleine foto´s, notities, schilderijen... Enig minpuntje voor mij is de iets stroever aanvoelende schrijfstijl, dit kan ook door de vertaling komen.

Sebald schetst in 6 hoofdstukken of essays het leven en werk van mij 5 onbekende schrijvers en 1 schilder. Net zoals in zijn meesterwerk 'Austerlitz' vermengt hij veel weetjes en citaten over de auteurs met kleine foto´s, notities, schilderijen... Enig minpuntje voor mij is de iets stroever aanvoelende schrijfstijl, dit kan ook door de vertaling komen.

steadybaum's review against another edition

5.0

This is perhaps his most academic published work, but it's still a highly personal and touching critic of various authors (and one painter) mostly focused on that enigmatic compulsion that drives writers to write. What makes this so damn good is just as you're about to trial away from his often meandering prose, Sebald jolts you back to consciousness with such a profound thought that it often stops you in your tracks and questions your own views and thoughts.

purslane's review

4.0

I was startled by the attribution, on page 66, of "Éducation sentimentale" to Stendhal. Was Sebald really capable of so grotesque a blunder? Owners of the German edition, speak up!

arirang's review against another edition

3.0

Sebald's own description of this work as merely "extended marginal notes and glosses" isn't as modest as it might first appear, and I wouldn't recommend this as a starting point for those interested in exploring Sebald.

But given his untimely death, any new translation of his work is more than welcome, and Sebald remains one of the greatest literary figures of the late 20th century.

The essays are clearly more enjoyable when you're more familiar with the work of the authors (Keller and Walser in my case), as compared to the many digressions in his novels, the essays do assume some prior knowledge of the author and subject.

Nevertheless, Sebald being Sebald, the ostensible subject is merely the starting point for his thoughts, and in many respect his reflections on the different authors can be read as a commentary on his own work.

But given his untimely death, any new translation of his work is more than welcome, and Sebald remains one of the greatest literary figures of the late 20th century.

The essays are clearly more enjoyable when you're more familiar with the work of the authors (Keller and Walser in my case), as compared to the many digressions in his novels, the essays do assume some prior knowledge of the author and subject.

Nevertheless, Sebald being Sebald, the ostensible subject is merely the starting point for his thoughts, and in many respect his reflections on the different authors can be read as a commentary on his own work.

More...