Take a photo of a barcode or cover

7 reviews for:

My Country, 'Tis of Thee: How One Song Reveals the History of Civil Rights

Claire Rudolf Murphy

7 reviews for:

My Country, 'Tis of Thee: How One Song Reveals the History of Civil Rights

Claire Rudolf Murphy

This picture book will be a great addition to the middle school library. It's bibliography alone shows the research. It tells a wonderful story (factual story) of a song and it's variations to serve people in despair, rejoice or unity. It encourages the reader to write their own verse. Great cross curricular activity.

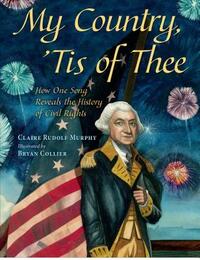

It doesn’t matter how long you’ve worked as a children’s librarian. It doesn’t matter how many books for kids you’ve read or how much of your life is dedicated to bringing them to the reading public. What I love so much about my profession is the fact that I can always be surprised. Take My Country, ‘Tis of Thee by Claire Rudolf Murphy as a prime example. I admit that when I glanced at the cover I wasn’t exactly enthralled. After all, this isn’t exactly the first book to give background information on a patriotic song or poem. We’ve seen a slate of books talking about "We Shall Overcome" over the years (one by Debby Levy and one by Stuart Stotts) as well as books on the Pledge of Allegiance or “The New Colossus”. So when I read the title of this book I admit suppressing a bit of an inward groan. Another one? Haven’t we seen enough of these? Well, no. Turns out we haven’t seen enough of them. Or, to be more precise, we haven’t seen enough good ones. What Murphy manages to do here is tie-in a seemingly familiar song to not just the history of America but to the embodiment of Civil Rights in this country itself. So expertly woven together it’ll make your eyes spin, Murphy brings us a meticulously researched, brilliant work of nonfiction elegance. Want to know how to write a picture book work of factual fascinating information for kids? Behold the blueprint right before your eyes.

The press for this book says, “More than any other, one song traces America’s history of patriotism and protest.” More than you ever knew. Originally penned in 1740 as “God Save the King”, the tune was sung by supporters of King George II. It soon proved, however, to be an infinitely flexible kind of song. Bonnie Prince Charlie’s followers sang it in Scotland to new verses and it traveled to America during the French and Indian War. There the colonists began to use it in different ways. The preacher George Whitefield rewrote it to celebrate equality amongst all, the revolutionary colonists to fight the power, the loyalists to celebrate their king, and even a woman in 1795 published a protest verse for women using the song. In each instance of the song’s use, author Claire Rudolf Murphy shows the context of that use and then writes out some of the new verses. Before our eyes it’s adapted to the Northern and Southern causes during The Civil War. It aids labor activists fighting for better pay. Women, Native Americans, and African-Americans adopt it, each to their own cause until, ultimately, we end with Barack Obama as president. Backmatter includes copious Source Notes documenting each instance of the song, as well as a Bibliography and Further Resources that are split between “If You Want to Learn More” and “Musical Links”. There is also sheet music for the song and the lyrics of the four stanzas as we know them today.

There’s always a bit of a thrill in being an adult reading information about history for the first time in a work for kids. I confess readily that I learned a TON from this book. But beyond that, it was the scope of the book that really captured my heart. That it equates patriotism with protest in the same breath is a wonderful move in and of itself. However, part of what I like so much about the book is that it is clear that our work is nowhere close to done. Here is how the book ends: “Now it’s your turn. Write a new verse for a cause you believe in. Help freedom ring.” Right there Murphy is making it clear that for all that the Obama’s inauguration makes for a brilliant capper to her story, it’s not the END of the story. People are still fighting for their rights. There are still causes out there worth protesting. Smart teachers, I hope, will brainstorm with their students the problems still facing equal opportunities in America today and will use this book to give kids a chance to voice their own opinions.

There’s a trend in nonfiction for kids right now that you’ll usually find in science picture books. When it comes to selling books to children, it can be awfully frustrating for an author to have limit their work to a very precise age range or reading level since, inevitably, your readership ages out of your book fairly quickly. The solution? Two types of text in the same book. The author will write a simple sentence on a page and then pair that with a dense paragraph of facts on the other. The advantage of this is that now the book reads aloud well to younger ages while still carrying information for the older kids. Or, put another way, children studying a subject can now get more information out of a single book if they’re interested and can disregard that same information if they’re not. I mention this because the layout of this book looks at first like that’s what Murphy was going for. You’ll have the factual information, followed by the new verses of the song. Then, at the end, in larger type will be a simple sentence. Yet as I read the book it became clear that what Murphy’s actually doing is using the large type sentences to draw connections from one page to another. For example, on the page about women marching for the right to vote, the section ends with the large type sentence, “But the privilege to vote didn’t extend to Native Americans, male or female” (a fact that, I am ashamed to say, I did not know). Turn the page and now we’re reading about the Native American struggles for Civil Rights and after reading the factual information the bolded sentence reads, “Equality did not exist for everyone in America.” Turn the page and there’s Marion Anderson. And it is at this point that Murphy draws her most brilliant connections between the pages. Marion Anderson leads to Martin Luther King listening to her Lincoln Memorial performance on the radio when he is ten, then we turn the page to King proclaiming “My country, ‘tis of thee” in his “I have a dream” speech, which then naturally ties into Aretha Franklin singing the song at the inauguration of Barack Obama. Amazing.

Now I’ve a funny relationship to the art of Bryan Collier. Sometimes I feel like he gives a book his all and comes out swinging as a result. If you’ve ever seen his work on [b:Uptown|1394477|Uptown|Bryan Collier|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1316727237s/1394477.jpg|829638] or Knock Knock or [b:Martin's Big Words|160943|Martin's Big Words The Life of Dr. Martin LutherKing Jr.|Doreen Rappaport|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1388461527s/160943.jpg|645566] or [b:Dave the Potter|8139824|Dave the Potter Artist, Poet, Slave|Laban Carrick Hill|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1317387255s/8139824.jpg|12936271] then you know what he’s capable of. By the same token, for every Uptown there’s a [b:Lincoln and Douglass|3943506|Lincoln and Douglass An American Friendship|Nikki Giovanni|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1397870901s/3943506.jpg|3989120] where it just doesn’t have that good old-fashioned Collier magic. I worried that maybe My Country, ‘Tis of Thee would fall into that category, particularly after seeing the anemic George Washington awkwardly placed on the book's cover. As it turns out, that’s probably the weakest image in the book. Go into it and you’ll see that Collier is in fine fettle for the most part. For example, in a section discussing how both the North and the South adopted this song and sang their own verses to it, Collier brilliantly overlays a soldier’s tent against a plantation background. Inside the tent are shots of the battle raging, letters from the soldiers spilling out over the sides like a fabric of their own. Turn the page and now the fields are bare, the Emancipation Proclamation having been declared, and the papers you see floating across the earth and into the sky all begin with “A Proclamation”. This is the kind of attention to detail that gets completely ignored in a work of nonfiction, even when the artist has taken a great deal of care and attention. It took me about five or six reads before I would notice the photographs of kids interspersed with the drawn people. And sure there’s the occasional misstep (the tea dumped by the Bostonians looks a bit more like the wings of birds than something you'd like to consume, and while Collier nails Aretha Franklin better than anyone I’ve ever seen he just can NOT get George Washington quite right) on the whole the book hangs together as well as it does because Collier knows what he’s doing.

I can already tell you that this book will not get the attention it deserves. And what it deserves is a place in every single classroom, library, and bookstore shelf in the nation. Yet this isn’t a work of children’s nonfiction that slots neatly into a pre-made hole. There’s nothing else really like this book out there. That it works as a brilliant piece of nonfiction as well as a smart as all get out piece of history and classroom ideas for teachers is clear. What it has to say about our country and our people and how they’ve fought for their rights should not, under any circumstances, be missed. It’s hard to write patriotic American fare for kids that doesn’t just sound like boosterism. This book manages to pull it off and you feel pretty good after it does. Do not miss it. Don’t.

For ages 7-12.

The press for this book says, “More than any other, one song traces America’s history of patriotism and protest.” More than you ever knew. Originally penned in 1740 as “God Save the King”, the tune was sung by supporters of King George II. It soon proved, however, to be an infinitely flexible kind of song. Bonnie Prince Charlie’s followers sang it in Scotland to new verses and it traveled to America during the French and Indian War. There the colonists began to use it in different ways. The preacher George Whitefield rewrote it to celebrate equality amongst all, the revolutionary colonists to fight the power, the loyalists to celebrate their king, and even a woman in 1795 published a protest verse for women using the song. In each instance of the song’s use, author Claire Rudolf Murphy shows the context of that use and then writes out some of the new verses. Before our eyes it’s adapted to the Northern and Southern causes during The Civil War. It aids labor activists fighting for better pay. Women, Native Americans, and African-Americans adopt it, each to their own cause until, ultimately, we end with Barack Obama as president. Backmatter includes copious Source Notes documenting each instance of the song, as well as a Bibliography and Further Resources that are split between “If You Want to Learn More” and “Musical Links”. There is also sheet music for the song and the lyrics of the four stanzas as we know them today.

There’s always a bit of a thrill in being an adult reading information about history for the first time in a work for kids. I confess readily that I learned a TON from this book. But beyond that, it was the scope of the book that really captured my heart. That it equates patriotism with protest in the same breath is a wonderful move in and of itself. However, part of what I like so much about the book is that it is clear that our work is nowhere close to done. Here is how the book ends: “Now it’s your turn. Write a new verse for a cause you believe in. Help freedom ring.” Right there Murphy is making it clear that for all that the Obama’s inauguration makes for a brilliant capper to her story, it’s not the END of the story. People are still fighting for their rights. There are still causes out there worth protesting. Smart teachers, I hope, will brainstorm with their students the problems still facing equal opportunities in America today and will use this book to give kids a chance to voice their own opinions.

There’s a trend in nonfiction for kids right now that you’ll usually find in science picture books. When it comes to selling books to children, it can be awfully frustrating for an author to have limit their work to a very precise age range or reading level since, inevitably, your readership ages out of your book fairly quickly. The solution? Two types of text in the same book. The author will write a simple sentence on a page and then pair that with a dense paragraph of facts on the other. The advantage of this is that now the book reads aloud well to younger ages while still carrying information for the older kids. Or, put another way, children studying a subject can now get more information out of a single book if they’re interested and can disregard that same information if they’re not. I mention this because the layout of this book looks at first like that’s what Murphy was going for. You’ll have the factual information, followed by the new verses of the song. Then, at the end, in larger type will be a simple sentence. Yet as I read the book it became clear that what Murphy’s actually doing is using the large type sentences to draw connections from one page to another. For example, on the page about women marching for the right to vote, the section ends with the large type sentence, “But the privilege to vote didn’t extend to Native Americans, male or female” (a fact that, I am ashamed to say, I did not know). Turn the page and now we’re reading about the Native American struggles for Civil Rights and after reading the factual information the bolded sentence reads, “Equality did not exist for everyone in America.” Turn the page and there’s Marion Anderson. And it is at this point that Murphy draws her most brilliant connections between the pages. Marion Anderson leads to Martin Luther King listening to her Lincoln Memorial performance on the radio when he is ten, then we turn the page to King proclaiming “My country, ‘tis of thee” in his “I have a dream” speech, which then naturally ties into Aretha Franklin singing the song at the inauguration of Barack Obama. Amazing.

Now I’ve a funny relationship to the art of Bryan Collier. Sometimes I feel like he gives a book his all and comes out swinging as a result. If you’ve ever seen his work on [b:Uptown|1394477|Uptown|Bryan Collier|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1316727237s/1394477.jpg|829638] or Knock Knock or [b:Martin's Big Words|160943|Martin's Big Words The Life of Dr. Martin LutherKing Jr.|Doreen Rappaport|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1388461527s/160943.jpg|645566] or [b:Dave the Potter|8139824|Dave the Potter Artist, Poet, Slave|Laban Carrick Hill|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1317387255s/8139824.jpg|12936271] then you know what he’s capable of. By the same token, for every Uptown there’s a [b:Lincoln and Douglass|3943506|Lincoln and Douglass An American Friendship|Nikki Giovanni|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1397870901s/3943506.jpg|3989120] where it just doesn’t have that good old-fashioned Collier magic. I worried that maybe My Country, ‘Tis of Thee would fall into that category, particularly after seeing the anemic George Washington awkwardly placed on the book's cover. As it turns out, that’s probably the weakest image in the book. Go into it and you’ll see that Collier is in fine fettle for the most part. For example, in a section discussing how both the North and the South adopted this song and sang their own verses to it, Collier brilliantly overlays a soldier’s tent against a plantation background. Inside the tent are shots of the battle raging, letters from the soldiers spilling out over the sides like a fabric of their own. Turn the page and now the fields are bare, the Emancipation Proclamation having been declared, and the papers you see floating across the earth and into the sky all begin with “A Proclamation”. This is the kind of attention to detail that gets completely ignored in a work of nonfiction, even when the artist has taken a great deal of care and attention. It took me about five or six reads before I would notice the photographs of kids interspersed with the drawn people. And sure there’s the occasional misstep (the tea dumped by the Bostonians looks a bit more like the wings of birds than something you'd like to consume, and while Collier nails Aretha Franklin better than anyone I’ve ever seen he just can NOT get George Washington quite right) on the whole the book hangs together as well as it does because Collier knows what he’s doing.

I can already tell you that this book will not get the attention it deserves. And what it deserves is a place in every single classroom, library, and bookstore shelf in the nation. Yet this isn’t a work of children’s nonfiction that slots neatly into a pre-made hole. There’s nothing else really like this book out there. That it works as a brilliant piece of nonfiction as well as a smart as all get out piece of history and classroom ideas for teachers is clear. What it has to say about our country and our people and how they’ve fought for their rights should not, under any circumstances, be missed. It’s hard to write patriotic American fare for kids that doesn’t just sound like boosterism. This book manages to pull it off and you feel pretty good after it does. Do not miss it. Don’t.

For ages 7-12.

Really enjoyed the history and various versions of the song. I found the 1795 version still appropriate today.

"God save each Female's right,

Show to her ravished sight

Woman is Free;

Let Freedom's voice prevail,

And draw aside the veil,

Supreme Effulgence hail,

Sweet Liberty."

Again in 1920:

"Our country, now from thee

Claim we our liberty,

In freedom's name.

Guarding home's altar fires,

Daughters of patriot sires,

Their zeal our own inspires,

Justice to claim."

Also an older labor song seems apt.

"My country, 'tis of thee,

Once land of liberty,

Of thee I sing.

Land of the Millionaire;

Farmers with pockets bare:

Caused by the cursed snare -

The Money Ring."

Wonderful ending with Marian Anderson's version sung on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Followed by Martin Luther King's version from the March on Washington and finally Aretha Franklin's version at Obama's inauguration.

"God save each Female's right,

Show to her ravished sight

Woman is Free;

Let Freedom's voice prevail,

And draw aside the veil,

Supreme Effulgence hail,

Sweet Liberty."

Again in 1920:

"Our country, now from thee

Claim we our liberty,

In freedom's name.

Guarding home's altar fires,

Daughters of patriot sires,

Their zeal our own inspires,

Justice to claim."

Also an older labor song seems apt.

"My country, 'tis of thee,

Once land of liberty,

Of thee I sing.

Land of the Millionaire;

Farmers with pockets bare:

Caused by the cursed snare -

The Money Ring."

Wonderful ending with Marian Anderson's version sung on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Followed by Martin Luther King's version from the March on Washington and finally Aretha Franklin's version at Obama's inauguration.

The song "America," more commonly known as "My Country 'Tis of Thee," is not the national anthem, but has played an important role throughout American history. This book traces its evolution from "God Save the King" in the 1740s, up through the various protests and civil rights struggles it has been used in. The author includes a variety of verses sung to the same tune, in the hopes that the United States would in fact become a "sweet land of liberty." A fascinating look at one song's changing place in history. Recommended for grades 3 and up.

Stunning, the progression of the text and how it connects the song and various civil rights events (for freedom, women, and races), is outstanding. The illustrations are lovely with painting and some collage to give them depth.

There are a lot more lyrics to this song than I realized. It was fun to sing all the different verses. I am not sure if kids will really pick it up, but it's a good overview of protest songs and how things in this country have changed.